Before I continue the series on theories of lexical exceptionality, I need to pause for a minute and review some work by Sharon Inkelas and colleagues: Inkelas and Cho 1993, Inkelas 1995, Inkelas and Orgun 1995, Inkelas et al. 1997. Inkelas and colleagues’ work has recently been generalized by Charles Reiss and colleagues (e.g., Bale et al. 2014, Reiss 2021, and Gorman & Reiss 2024, the latter under review and available on LingBuzz), turning Inkelas’s original idea into a generalized theory of exceptionality, and I’ll review that before long, in a separate post. I don’t consider the Inkelas(verse) approach to represent a complete theory of exceptionality and so I am not presenting them as such.

Preliminaries

A few other caveats are in order before I begin. First, underspecification is hardly a novel idea: it wasn’t even a new one when it first became a major subject of consideration in the 1980s. The American structuralists espoused the axiom of biuniqueness, which in some sense presages underspecification. At a high level, biuniqueness holds that there is a one-to-one correspondence between the phonemic and allophonic (“phonetic”) level. In practice, this rules out the correspondence modern phonologists term neutralization, in which the allophones of two distinct phonemes overlap. Formally, neutralization occurs when two phonemes /x, y/ (where x ≠ y) both have an allophone [z] (regardless of whether z ∈ {x, y} or not). A well-known example of neutralization in many dialects of English (Joos 1942) is the intervocalic [ɾ] in writer and rider. On the basis of write and ride, one would be tempted to set this up as an allophone of /t, d/, respectively, but this neutralization violates biuniqueness.1

This axiom is generally consonant with the overall late structuralist search for a deterministic discovery procedure. One is tempted to liken the late structuralists to alchemists, a workable discovery procedure to the philosopher’s stone, and their failed search to the magnum opus.

The structuralists imposed no biuniqueness constraint on a more abstract, poorly-theorized “morphophonemic” level which would, apparently, contain generalizations like English post-tonic flapping. The morphophonemic level was poorly theorized so how exactly this ought to work is a little unclear. The archiphoneme, popularized by the Prague School structuralists Nikolai Trubetzkoy and Roman Jakobson, suggests one possibility. An archiphoneme is a sort of morphophonemic symbol not yet specified for features which are to be later neutralized. By convention they are denoted in derivations with capital letters not otherwise used for IPA symbols. In the case of post-tonic flapping, one might write the flap character as the arciphoneme /D/, and propose allomorphic or morphophonemic rules which insert it into writer and rider in place of /t, d/. In the Inkelasverse, archiphonemes are simply a way to annotate underspecification (here presumably of the Voice feature that distinguishes /t, d/), and their convention of using capital letters for underspecified segments calls back to this tradition.

Given the archiphonemic “escape hatch” and noting that many late structuralists also published influential morphonemic sketches (e.g., Bloomfield 1939, Chomsky 1951, Hamp 1953), one might reasonably question how closely held the biuniqueness axiom really was at the time. Chomsky and Halle (e.g., Halle 1959, Chomsky 1964, Chomsky & Halle 1965) argue that biuniqueness introduces a great deal of duplication, with morphophonemic rules reprising the same generalizations as phonemic ones. They thus propose to reject biuniqueness and to merge the phonemic and morphophonemics into a single level of description. Yet we see that Chomsky and Halle got a lot of pushback (see cited papers) from late structuralist éminences grises, so their rejection of biuniqueness was not uncontroversial at the time.

Secondly, there are a rather-distinct set of arguments, not considered in any detail by Inkelas and colleagues, for surface underspecification. Keating (1988), for example, provides phonetic arguments for the use of underspecification. If one permits underspecification on the surface, it is not obvious why it should not also be permitted in earlier stages of the derivation.

Jumping forward a bit, underspecification theory received a lot of attention in the late 1980s and early 1990s, but interest seems to have waned after Donca Steriade’s chapter in the first Blackwell Handbook of Phonology (1995), which reviews a number of theories of underspecification, taking a dim view of the overall enterprise. Steriade’s review is very good—I would recommend you read it if you haven’t—but as I remember it, the critiques mostly do not apply to the Inkelasverse.

Inkelas and Cho 1993

Inkelas and Cho (1993; henceforth I&C) propose a theory in which underspecification (or its absence, prespecification) is used to derive a number of interesting effects. Their slogan is: prespecification is inalterability; one might add that thus underspecification is mutability.

I&C begin with a common-place observation that geminates are often immune to processes which singleton segments undergo. They review attempts to derive this effect using autosegmental representations and various rule-application conventions, but conclude that no set of representations and conventions work in general. I&C propose that it is not geminate status per se but rather a more general convention of prespecification that is at play.

For example, in certain dialects of Berber, singleton consonants spirantize (and voice if they are pharnygealize), but geminates are always voiceless stops. Note that this is not merely a static generalization: the singleton and geminate forms are morphologically related, because these languages have templatic morphology and certain inflectional and/or derivational forms call for consonants to be geminated. Noting that Continuancy and Voice are generally non-contrastive for consonants, I&C propose:

(1) Berber consonants (after I&C, §5.2.1):

a. consonants, either singleton or geminate, are not underlyingly specified for Continuant or Voice.

b. a geminate-specific feature-filling rule inserts [−Continuant], and if [+Pharyngeal], [-Voice].2

c. a later feature-filling rule inserts [+Continuant], and if [+Pharyngeal], [-Voice].

Crucially, rule (1b) bleeds rule (1c) by virtue of being feature-filling, and thus geminates are exempt. This opens up a few new avenues to consider.

First, they note that some of the relevant dialects of Berber have apparent lexical exceptions: voiced, continuant geminates […ɣɣ…]. They propose that these apparent exceptions can be prespecified [+Voice, +Continuant]. Given the condition that rules (1bc) are feature-filling, these “exceptions” are not really exceptional at all! I&C note (§5.7) that this is a highly-restrictive theory of lexical exceptionality compared to earlier approaches but claim some advantages as well.

In a footnote (p. 556, fn. 26), I&C note that they cannot handle cases in which “exceptionality takes the form of failure to trigger, rather than failure to undergo, a rule” which “remain a problem for us until they can be resolved in a representational fashion”.

Secondly, they observe that the account given in (1) is in no way specific to geminate status. It requires, of course, that (1b) can target geminates to the exclusion of singletons, but this follows from their assumption that geminates are prespecified with two moras and a standard interpretative procedure; i.e., if a rule specifies that a target is linked to two moras, a segment linked to only one is not a target.3 Thus, this account generalizes to instances of “inalterability” which are not related to geminacy. For example, exceptions to vowel harmony in Turkish may simply reflect pre-specified Back and Round features which are “inalterable” with respect to structure-filling harmony rules.

Third, they note that this sort of account cannot be applied to structure-changing rules, and find no counterexamples. Indeed, they suggest, as many others have, that so-called structure-changing rules are decomposed into a feature-delinking rule followed by feature-insertion (or spreading) rule.

I note that a few examples given by I&C, such as Klingenheben’s Law in Hausa, are of no obvious relevance to synchronic phonology. For example, this law can be thought of as a diachronic change, which may or may not have had a synchronic analogue in the past, or as a static phonotactic constraint deriving (diachronically) from said change, which may not have any synchronic force.

I&C take their proposal to be an instance of Kiparsky’s notion of radical underspecification (RU), according to which features are binary and only marked feature values are present underlyingly. Indeed, their account of inalterability as prespecification is a good argument against privativity and thus for binarity. For instance, if Voice is privative (and thus equivalent to [+Voice] in a binary system), then there is no way for (1b) to block (1c). However, in my opinion RU does not acquit itself well in I&C’s account. They note some cases where it conflicts with their assumptions about feature markedness. Furthermore, it’s not clear to me what the presence of prespecified faux-exceptions I&C posit like the […ɣɣ…]s in Berber dialects means for RU.

Inkelas 1995

Inkelas (1995) attempts to relate some of I&C’s earlier insights to ideas in Optimality Theory (OT).

Inkelas begins with some now-famous data from Turkish. There are three kinds of consonant-final roots: those in which the final consonant is consistently voiceless (e.g., sanat/sanatı ‘art’; the second form is the accusative), those which are consistently voiced (etüd/etüdü ‘etude’), and those which alternate (e.g., kanat/kana[d]ı ‘wing’). Short of root suppletion, it is hard to imagine how one would handle this three-way distinction without making use of underspecification. Inkelas proposes, naturally, that the alternating kanat is underlyingly /kanaD/, where /D/ denotes a coronal stop underspecified for Voice, and the non-alternating final consonants are prespecified for Voice. This is once again an instance of prespecification as inalternability, because presumably the processes which insert final voice specifications are feature-filling and thus do not apply to fully-specified root-final /t, d/.

Inkelas considers but rejects an alternative using morpheme-level exceptionality, an idea pursued in some detail in SPE and subsequent work and still in vogue in OT circles. She suggests this is no different than introducing morpheme-specific multiple grammars, and that with this tool in place, it is hard to know when to stop proliferating grammars. For instance, while it might be sensible to treat one of the three voicing patterns in Turkish as exceptional, giving us two grammars, one could just as well derive all three patterns using the same underlying stem-final /d/ and three different grammars. In my opinion, one might equate “exceptionality” with the lack of productivity, and thus use standard diagnostics (e.g., perhaps child product errors, wug-tests, or evidence from loanword adaptation) and/or theories (e.g., Tolerance) to address this issue, and one might also argue against grammar proliferation on evaluation-metric grounds. But I agree that the morpheme-level theory is radically underconstrained without additional theoretical commitments along these lines.

At the same time, Inkelas also claims the use of underspecification to account for such phenomena as unconstrained. She suggests that the notion of lexicon optimization (LO), slightly revised, provides an appropriate constraint.

She points out that LO, as originally defined, is intended to pick out an “faithful” UR for cases of pure allophony, and proposes a variant of LO which is sensitive to the presence of alternations (her 16). Basically, the principle is to pick as the UR of a morpheme M the form which is most harmonic with respect to all allomorphs of M. While I understand the motivation here, this does not seem to be formal enough to implement. For instance, let us suppose S is the set of surface forms of M, and let I be the set of candidates for the UR. Note also that S and I may be disjoint (i.e., elements of I need not be observed surface forms), an assumption which will become important in a moment. Let us assume that, somehow, the grammar is already known. Finally, suppose that the child has computed, for each hypothetical UR in I, a tableau for surface forms s with respect to the grammar; there will be |S| × |I| such tableaux. Then, for candidate UR i, how exactly is the child to combine the harmony scores of |S| tableaux so that it can be compared to the scores for candidate UR j? In the cases Inkelas considers, |I| = 3 (because she considers, e.g., in the Turkish case, /t, d, D/), and the winning i harmonically bounds the other candidate URs, but it is not clear to me that this is generally true. However, I put these big issues aside for sake of argument.

Inkelas argues that, in the case that there are predictable alternations, this revised form of LO will select a UR with the underspecified segment with respect to the alternating features, and the UR will be fully specified otherwise. For instance, if Turkish in fact has high-ranked constraints motivating word-final plosive devoicing, it will select Voice-underspecified /kanaD-/ for kanat, whereas non-alternating sanat and etüd will be fully specified as /t, d/ respectively. This, she shows, is also the case in simpler two-way alternations, like ATR harmony in Yoruba: she argues that the revised form of LO will leave prefix vowels which undergo ATR harmony underspecified for ATR.

A key idea here is that underspecification is not driven by universal principles (as in earlier markedness-based approaches) but is quite intimately tied to the grammar. Indeed, her form of LO depends on the child having already converged on a grammar before setting (or perhaps “optimizing”) the URs.

This paper concludes with a number of implications for the proposal. She compares and constrasts her proposal with the Prague school archiphoneme, which shares some important similarities. More importantly, she notes that underspecification which gives rise to ternarity is an argument against privativity, since there is no way to derive ternarity in a privative feature system. I would add that, since there does not seem to be any principle that governs which features can be underspecified nor any evidence suggesting that some features cannot, there is no evidence that any features are privative.

Inkelas’s proposal is an dialogue with (her advisor) Kiparsky’s notion of absolute neutralization. Kiparsky (1973) introduces this notion to critique SPE‘s roundly-criticized notion that nightingale contains an underlying, never-surfacing velar fricative /x/ which blocks trisyllabic shortening, and what he actually critiques is positing an underlying /x/ which is deleted in all surface forms. Here the “absolute” part of “absolute neutralization” could easily be referring to the fact that /x/ is not merely neutralized, but entirely deleted. However, his proposed remedy, the alternation condition, is stated more broadly:

(2) Alternation Condition (Kiparsky 1973:65): neutralization processes cannot apply to all occurrences of a morpheme.

This makes it reasonably clear to me that he intends “absolute” to refer to the fact the neutralization (which just happens to be deletion in this case) occurs in all cases (i.e., across the board).

It seems to me that Inkelas’s proposal not only conforms to (2), at least in simple cases, it actually provides a glimpse into how the child builds URs that conform to (2). This is a marked improvement.

While Inkelas seems to view her proposal as closely tied to OT and its assumptions, I do not necessarily agree: I would argue that any coherent theory of phonology will have some analogue to lexicon optimization, a point already anticipated in the SPE-era evaluation metric.

Inkelas and Orgun 1995

Inkelas and Orgun (1995; henceforth I&O) attempt to merge the previous proposals about underspecification into a larger theory of morphological structure. Their object of study is a partial sketch of Turkish morphophonology, and as such, interacts with Inkelas and colleagues’ earlier discussion of various phonological phenomena in Turkish.

While it is not all that germane to the Inkelasian theory of underspecification, I should briefly summarize the novel elements of their morphological theory. First, I&O propose that morphemes are “prespecified” for the levels in which they are introduced. Secondly, I&O propose that these levels may have different phonology. Neither of these proposals is controversial, and echo, e.g., Siegel (1979 [1974]). More interestingly, though, they propose that (partial) forms are subject only to the phonology of the levels at which they derive, a principle they call level economy. Level economy means that, for example, a form which lacks level 3 morphemes is not subject in any way to level 3 morphology, and when a level 2 morpheme is inserted, the resulting (possibly partial) form is not subject to level 1 morphology, and so on.

One case of relevance to underspecification is their new take on Turkish ternary voicing (I&O:776f.), discussed earlier. They claim that monosyllabic roots are all of the non-alternating variety: e.g., at/atı ‘horse’ or ad/adı ‘name’. Their analysis of this restriction is novel: they propose that a hypothetical /aD-/ would be identical to at/atı because of the interaction a between final-consonant invisibility, a minimality condition which prevents this from applying to monosyllables, and level prespecification to exempt certain stems from minimality and thus preventing final-consonant invisibility.

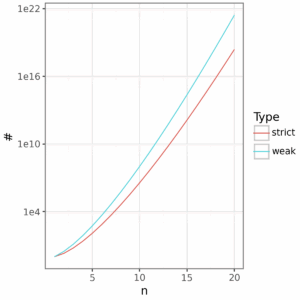

Later in the paper (op. cit.:787f.) it is revealed that this generalization has many exceptions. I&O search a Turkish dictionary for plosive-final monosyllables, and filtering out those not known to the second author, a native speaker of Turkish. In total, there are 4 monosyllables ending in a plosive which are voiced and non-alternating, 77 which are voiceless, and 17 which are alternating. I&O propose that the 17 alternating stems are prespecified as level 1 morphemes, which ultimately prevents them from undergoing devoicing at level 1.

I for one am not convinced there are any meaningful generalizations here. First, these frequencies could very well be historical accident (a point made in a different context by Inkelas et al. 1997:402), and there is no evidence children acquiring Turkish attend to them. Indeed, the other elements of their analysis (minimality and final-consonant invisibility) are either motivated by other exception-filled generalizations (e.g., their analysis of velar drop), and some of these are static conditions on URs which may also be ignored by children. Secondly, it is not clear why I&O derive the “exceptionality” of alternating final plosives from their morphological prespecification, whereas non-alternating voiced stems, which are much rarer, are instead treated phonologically. I&O write that in their analysis, “[n]onalternating voiced final plosives are exceptional among monosyllables…we account for them through the prespecification of [+voice]”. But by their analysis alternating final plosives are in the same sense “exceptional” in lacking a voice specification: their use of level prespecification solves a problem that I&O have themselves introduced by making feature-changing devoicing as a level 1 process.

In conclusion, I much prefer the simpler analysis of ternary voicing provided by Inkelas (1995), which does not make mention of final-consonant invisiblity, minimality, or level prespecification.

Inkelas et al. 1997

In our final paper, Inkelas et al. (1997) provide a detailed critique of morphemic exceptionality, which they call cophonology. Much of their discussion is based on ternary voicing in Turkish, and a proposed static generalization known as labial attraction; the second is the ternary voicing alternation.

You have already heard what both Inkelas and colleagues and I have to say about ternary voicing; it is interesting in this regard that they cite, but do not rehearse, the more complex (and IMO problematic) analysis proposed by I&O two years earlier.

But before I tell you what they have to say, I should briefly discuss labial attraction. As it happens, chapter 3 of my dissertation (Gorman 2013) actually discusses labial attraction in some detail. This is in the context of a larger critique of phonotactic theory and its relation to ordinary phonology: I am in this work claiming that many phonotactic patterns derive directly from the occulting effect of phonological processes, and I argue that others are not necessarily internalized by speakers. I first perform a simple statistical analysis of labial attraction in Turkish using a digital lexicon of the language (Inkelas et al. 2000). In the analysis, I compare the frequency of disharmonic …aCu… to harmonic …aCı… sequences, conditioned on whether the intervening consonant is labial or not. As it happens, there is significantly more disharmony when the intervening consonant is non-labial, suggesting the proported lexical trend is not a trend at all.4 Secondly, I statistically reanalyze the results of a nonce word judgment task conducted by Zimmer (1969).5 This reanalysis finds that Zimmer’s Turkish speakers fails to find a significant effect of labial harmony: that is, they do not prefer disharmonic, labial-attraction nonce words like pamuz over harmonic nonce words like pamız. Pace Lees and Zimmer, there is no evidence that labial attraction exists, and subsequent theorizing based on it is fruit of the poisonous tree. Indeed, Inkelas et al. are also skeptical at various points about labial attraction. For instance, they write that “because of Lexicon Optimization, the lexicon of Turkish will look the same whether or not Labial Attraction is actually part of the grammar” (op. cit.:412; emphasis theirs), and provide tableaux establishing this point. I agree.

Let us put this all aside for sake of argument. What do Inkelas et al. propose?

First, they again endorse the use of underspecification for ternary alternations proposed by I&C and Inkelas (1995), and the use of underspecification for predictable alternations and prespecification elsewhere as proposed by Inkelas (1995). They express some concern whether prespecification can be made consistent with certain types of synchronic chain shifts.

Secondly, Inkelas et al. also tentatively endorse the notion that “structure-changing” rules ought to be decomposed into structure-deleting and structure-inserting rules; this idea, which has a long precedent, plays a major role in our recent work on Substance-Free Logical Phonology (LP). They express some concern as to whether this reintroduces “conspiracies” where structure-deleting and structure-inserting rules have similar contexts. I for one disregard this concern because I don’t regard Kisseberth’s (1970) notion of conspiracy to be sufficiently formal, and phonologists after Kisseberth have engaged in a sort of motivated cognition in which their intuitions about what is or is not a conspiracy are unduly informed by what kinds of redundancies they are prepared to excise. Let us, for sake of argument, formalize this notion as related to the decomposition proposed by Inkelas et al., using the tools of LP. A definition follows. Let us suppose that there exist two rules of the following form, where A, C, and D are natural classes and B is a set of feature specifications.

(4) A ∖ B / C _ D

(5) A ⊔ B / C _ D

Then, if (4-5) are both present in some grammar and there is no evidence to establish that some other rule applies after (4) but before (5), we will say that (4-5) are in a conspiracy. Our experience applying LP to real data suggests such conspiracies do occur but are not the norm. For instance, consider Gorman & Reiss’s (2024) analysis of Cervara metaphony. First, I repeat Gorman & Reiss’s rules (20-21) as (6-7); these are clearly in a conspiracy as defined above.

(6) [-Low, +ATR] ∖ {-High} / _ C0 [+High]

(7) [-Low, +ATR] ⊔ {-High} / _ C0 [+High]

The same is true of Gorman & Reiss’s rules (24-25). But this is not always the case; rules (19), (23) and (26-28) are all unification rules which are dissimilar to any subtraction rule. And it should be noted that Gorman & Reiss’s analysis is essentially a translation of an earlier analysis (Danesi 2022) into LP, and was not engineered to reach this conclusion.

Third, Inkelas et al. rehearse, in longer form, Inkelas’s (1995) earlier argument against cophonologies, and adds in a problem I discussed in an earlier post: cophonologies have little to say about cases in which one segment in a morpheme is exceptional with respect to some process but another is not. Their example, Spanish diphthongization, is not the best one, but Rubach’s discussion of yer-deletion in Polish, discussed in that post, is more germane.

Endnotes

- Interestingly, as far as I can tell, Joos, a structuralist in good standing at the time, does not seem to have noticed the apparent violation of biuniqueness nor does he draw attention to the “morphophonemic” nature of flapping forced by biuniqueness.

- I grant, sake of argument, that this “if pharyngeal, voiceless” sub-condition, reminiscent of the largely-forgotten SPE-era angle-bracket notation, can be encoded within a single rule, but I would probably prefer to split (1b) into two rules: one for spirantization and one for pharyngeal voicing, and similarly for (1c).

- I&C adopt moraic theory, but I suspect that one could do something quite similar with X-theory. I&C also note that intervocalic geminates occupy both coda and onset position and this can have a similar effect. This works so long as syllable position is determined (i.e., syllables are parsed) before the relevant rules apply; it doesn’t require that it be prespecified.

- There are other comparisons I could have done here, but I thought this was the most salient comparison. This comparison controls for the frequency at which a is followed by a [+High, +Back] vowel in the following syllable, and thus directly focuses attention on labial attraction as a source of exceptions to harmony.

- My reanalysis was necessary because while Zimmer reports that he conducted a statistical analysis of the data, he provides no useful details about his statistical procedures.

References

Bale, A., Papillon, M., and Reiss, C. 2014. Targeting underspecified segments: a formal analysis of feature-changing and feature-filling rules. Lingua 148: 240-253.

Bloomfield, L. 1939. Menomini morphophonemics. Travaux de Cercle Linguistique de Prague 8: 105-115.

Chomsky, N. 1951. Morphophonemics of Modern Hebrew. Master’s thesis, University of Pennsylvania.

Chomsky, N. 1964. Current Issues in Linguistic Theory. Mouton.

Chomsky, N. and Halle, M. 1965. Some controversial questions in phonological theory. Journal of Linguistics 1: 97-138.

Danesi, P. 2022. Contrast and phonological computation in prime learning: raising vowel harmonies analyzed with emergent primes in radical substance free phonology. Doctoral Dissertation, Université Côte d’Azur.

Gorman, K. 2013. Generative phonotactics. Doctoral dissertation, University of Pennsylvania.

Gorman, K., and Reiss, C. 2024. Metaphony in Substance Free Logical Phonology. Submitted. URL: https://lingbuzz.net/lingbuzz/008634.

Halle, M. 1959. The Sound Pattern of Russian. Mouton.

Hamp, E. 1953. Morphophonemes of the Keltic mutations. Language 27: 230-247.

Inkelas, S. and Cho, Y.-M. 1993. Inalterability as prespecification. Language 69: 529-574.

Inkelas, S., 1995. The consequences of optimization for underspecification. In Proceedings of the 25th Meeting of the North East Linguistic Society, pages 287-302.

Inkelas, S. and Orgun, C.O., 1995. Level ordering and economy in the lexical phonology of Turkish. Language 71, 763-793.

Inkelas, S., Orgun, C.O., and Zoll, C. 1997. The implications of lexical exceptions for the nature of grammar. In I. Roca (ed.), Derivations and Constraints in Phonology, pages 393-419. Clarendon Press.

Inkelas, S. Küntay, A., Orgun, C.O., and Sprouse, R. 2000. Turkish Electronic Living Lexicon (TELL). Turkic Languages 4: 253-275.

Joos, M. 1942. A phonological dilemma in Canadian English. Language 18(2): 141-144.

Keating, P. 1988. Underspecification in phonetics. Phonology 5:275-292.

Kiparsky, P. 1973. Phonological representations: Abstractness, opacity and global rules. In O. Fujimura (ed.), Three Dimensions of Linguistic Theory, pages 57-86. TEC.

Kisseberth, C. W. 1970. On the functional unity of phonological rules. Linguistic Inquiry 1(3): 291-306.

Lees, R. B. 1966a. On the interpretation of a Turkish vowel alternation. Anthropological Linguistics 8: 32-39.

Lees, R. B. 1966b. Turkish harmony and the description of assimilation. Türk Dili Araştırmaları Yıllığı Belletene: 279-297.

Siegel, D. 1979. Topics in English Morphology. Garland Publishing.

Steriade, D. 1995. Underspecification and markedness. In J. Goldsmith (ed.), The Handbook of Phonological Theory, pages 114-174. Blackwell.