Neural network cognitive modeling had a brief, precocious golden era between 1986 (the year the Parallel Distributed Processing books came out) and maybe about 1997 (at which point the limitations of those models were widely known…though I’m little fuzzier about when this realization settled in). During that period, I think it’s fair to say, a lot of people got hired into the faculty, in psychology and linguistics in particular, simply because they knew a bit about this exciting new approach. Some of those people went on to do other interesting things once the shine had worn off, but a lot of them didn’t, and some of them are even still around, haunting the halls of R1s. I think something similar will happen to the new crop of LLMologists in the academy: some have the skills to pivot should we reach peak LLM (if we haven’t already), but many don’t.

Asides

Hiring season

It’s hiring season and your dean has approved your linguistics department for a new tenure line. Naturally, you’re looking to hire an exciting young “hyphenate” type who can, among other things, strengthen your computational linguistics offerings, help students transition into industry roles and perhaps even incorporate generative AI into more mundane parts of your curriculum (sigh). There are two problems I see with this. First, most people applying for these positions don’t actually have relevant industry experience, so while they can certainly teach your students to code, they don’t know much about industry practices. Secondly, an awful lot of them would probably prefer to be a full-time software engineer, all things considered, and are going to take leave—if not quit outright—if the opportunity ever becomes available. (“Many such cases.”) The only way to avoid this scenario, as I see it, is to find people who have already been software engineers and don’t want to be them anymore, and fortunately, there are several of us.

News from the east

I am a total sucker for cute content from East Asia. I loved to watch Pangzai do his little drinking tricks. I love to hear what the “netizens” are up to. I love the greasy little hippo. I love the horse archer raves. I even love the chow chows painted as pandas. It’s delightful. Is this propaganda? Maybe; certainly it’s embedded a larger matrix of Western-oriented soft-power diplomacy. (That’s why we have so many Thai restaurants.) But I suppose I’m blessed to live in a time where you can get so much cute news from halfway across the world.

Learned tokenization

Conventional (i.e., non-neural, pre-BERT) NLP stacks tend to use rule-based systems for tokenizing sentences into words. One good example is Spacy, which provides rule-based tokenizers for the languages it supports. I am sort of baffled this is considered a good idea for languages other than English, since it seems to me that most languages need machine learning for even this task to properly handle phenomena like clitics. If you like the Spacy interface—I admit it’s very convenient—and work in Python, you may want to try thespacy-udpipe library, which exposes the UDPipe 1.5 models for Universal Dependencies 2.5; these in turn use learned tokenizers (and taggers, morphological analyzers, and dependency parsers, if you care) trained on high-quality Universal Dependencies data.

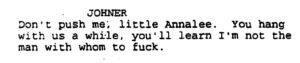

Pied piping and style

I find pied-piping in English a bit stilted, even if it is sometimes the prescribed option. Consider the following contrast:

(1) I’m not someone to fuck with.

(2) I’m not someone with whom to fuck.

In (1) the preposition with is stranded; in (2) it is raises along with the wh-element. What are your impressions of a speaker who says (2)? For me, they sound a bit like a nerd, or perhaps a cartoonish villain. I thought about this the other day because I was watching Alien Resurrection (1997)—it’s okay but not one of my favorite entries in the Weyland-Yutani cinematic universe—and one of the first bits of characterization we get for mercenary “Ron Johner”, played by badass Ron Perlman, is the following bit of dialogue (here taken directly from Joss Whedon’s screenplay):

This would work if Johner was a sort of evil genius, or if it was some kind of callback to something earlier, but I think this is probably just unanalyzed language pedantry ruining the vibe a little.

High school as signaling behavior

When you meet an adult for the first time in Cincinnati—where I grew up—it is customary to ask them where they went to high school. Even though I have had basically nothing to do with Cincinnati since I reached the age of majority, I can learn so much about someone by learning they went to St. Ursula, or Walnut Hills, or Elder, Summit Country Day, or Wyoming. (This is helped along by the fact that Cincinnati is, for historical reasons, rather Catholic.) It’s one of the first things I ask born and raised New Yorkers too, and it tends to yield a lot of information. I know half a dozen graduates of Bronx Science (including the president of my college); I believe David Pesetsky is one of several well-known linguists who attend Horace Mann; Hunter High is also a very promising sign, as is Stuyvesant. I even know about some of the elite high schools of Illinois at this point.

While virtually all the focus on “elite institutions” is directed at undergraduate colleges, I think this is something of a misdirection. While this may seem self-serving, I think high school choice might be a stronger signal than college choice, at least in parts of the country where it is common for one (with the help and possibly financial support of one’s parents, of course) to more or less pick a high school, with many magnet and private options.

My personal experience bears this out. I went to a very good suburban public school system (Lakota) until I was 14 and the strongest students at 14 who continued on to high school in that system are not living particularly impressive lives. In contrast, my class at my very good Catholic high school (St. Xavier) includes, among other impressive individuals, two centimillionaires (though one of those two is a phony and a scoundrel). I for one did not gain much personal ambition from St. Xavier, but I did acquire a love of learning (as someone once described it to me, “a pseudo-erotic attachment to knowledge”). Also, without any particular intentionality, I attended a good (but not selective) “R1” public college, and I feel like high school left me particularly well-positioned to take advantage of it. I didn’t even seriously consider elite colleges; I grew up in a solidly middle class family where there was no particular knowledge of elite institutions, to the point that I didn’t even find out what the Ivy League was until after I’d been accepted to Penn for my PhD. Had I been drawn from a slightly higher class stratum, I might have applied to Ivys, or at least one of those pricy private liberal arts schools on the East Coast like Vassar, and had I done so, I would have taken on an onerous load of personal debt in the process. And for what? It wouldn’t have made me any better a scholar.

Stop capitalizing so much

One of the absolute scourges of student writing is the tendency to capitalize just about every multi-word noun phrase. The rule in English is pretty simple: you only capitalize proper names, and these are, roughly, the names of people, locations, or organizations. Technical concepts do not qualify. It doesn’t matter if it’s part of an acronym: we capitalize the acronym but not necessarily the full phrase. Natural language processing is not a proper name; cognitive science isn’t either; logistic regression certainly is not a proper name nor is conditional random fields or hidden Markov model or support vector machine or…

Rich people shouldn’t drive

I don’t understand why the filthy rich ever drive. Sure, I get why Ferdinand Habsburg gets into the Eva cockpit: an F1 race is the modern-day tournament. But driving is a dangerous, high-liability, cognitively taxing activity and it’s easy for the rich to offload those hazards to a specialist. I don’t understand why, for example:

- Warren Buffett (alleged net worth $138B) supposedly drives his own older Cadillac to the office (though maybe not anymore, given that he’s now 93).

- “Little” Sam Altman (alleged net worth $1B) drives a low-to-the-ground sports car through stop-and-go traffic in downtown Palo Alto (it’s giving Dukakis).

- “Bumpin’ dat” Justin Timberlake (alleged net worth $250M) got busted for a DUI in Long Island.

- Alec Baldwin (alleged net worth $70m) settled out of court with a guy he allegedly punched in the jaw over a parking spot.

In the unlikely event that I hit centimillion status, the first thing I’m doing is buying a black, under-the-radar towncar and hiring a chaffeur with good personal recommendations. And before that, when I enter decamillion territory, I’m just calling UberXen. No alternate-side parking, no DUIs for me. I don’t know about Justin, but surely Warren and Sam have something better to do than be behind the wheel. They could be power napping, meditating, watching the market, or catching up on X (“the everything app”) the back of their car instead.

The presupposition of “recognize”

There’s an interesting pragmatics thing going on in the official statement ex-first lady Melania Trump put out after her husband was grazed by a sniper’s bullet. (The full statement is here if you care; it’s not very interesting overall.) However I was drawn to an interesting violation of presupposition in the document:

A monster who recognized my husband as an inhuman political machine attempted to ring out Donald’s passion – his laughter, ingenuity, love of music, and inspiration.

A few things are going on here; let me put aside the awkward non-parallelism of laughter vs. love of music vs. ingenuity and inspiration and note that the verb she wants in the embedded clause is wring out (figuratively, to extract by means of forceful action) not ring out. But the more interesting one is the use of recognized. To say that the shooter recognized Donald Trump as an inhuman machine presupposes that the speaker agrees with this assessment; or perhaps more generally that it is in the common ground that Donald Trump is an inhuman machine, at least in my idiolect. There is nothing in the text or subtext of the statement suggesting she views her husband as a monster, despite the long and tedious tradition of trying to “read resistance” into the wives of right-wing American politicians. For me verbs like misconstrued or mistook presupposes the opposite, that the speaker and/or common ground disagrees with this assessment, and that’s what I suppose Mrs. Trump meant to say here. I don’t blame Mrs. Trump for this; English is not her first language, though she speaks it quite well. But she’s famous and rich enough that she ought to employ a PR professional or lawyer to proof-read public statements like I’m sure Mrs. Obama or Mrs. Bush do.

Medical bills

Starting about two years ago, I got an unexpected medical bill in the mail. The amount wasn’t very high, but I was quite frustrated and annoyed. First, this was from a local College of Dentistry, where most procedures are free for the insured (and probably not insured too); there was no “explanation of benefits” that explained this was a co-pay, or that my insurance only covered some portion. Secondly, I hadn’t been to the College of Dentistry in quite a while, so I had no idea which of the various procedures this was or even what day I received the billed service. Third, there was no way to get more information: the absolute worst thing about this provider is that the administrative staff are some of the most overloaded and overworked people I have ever seen, and I have witnessed them just let the phone ring because they’re dealing with a huge line of in-person patients (some of whom are bleeding from their mouth). So I didn’t pay it. After a while though, the bills continued and I started to worry. Was I wasting paper for no reason? Would this harm my credit score? So I put about an hour into finding a way to actually get in touch with the billing office: turns out this was a Google Form buried somewhere on a website, and if you fill it out, a someone calls you (in my case, within the hour!), looks up your chart, and can tell you the date of service and why you were billed. Why they didn’t just include this in the bill in the first place? I have to imagine this makes it ever harder for the College to actually collect on these debts.